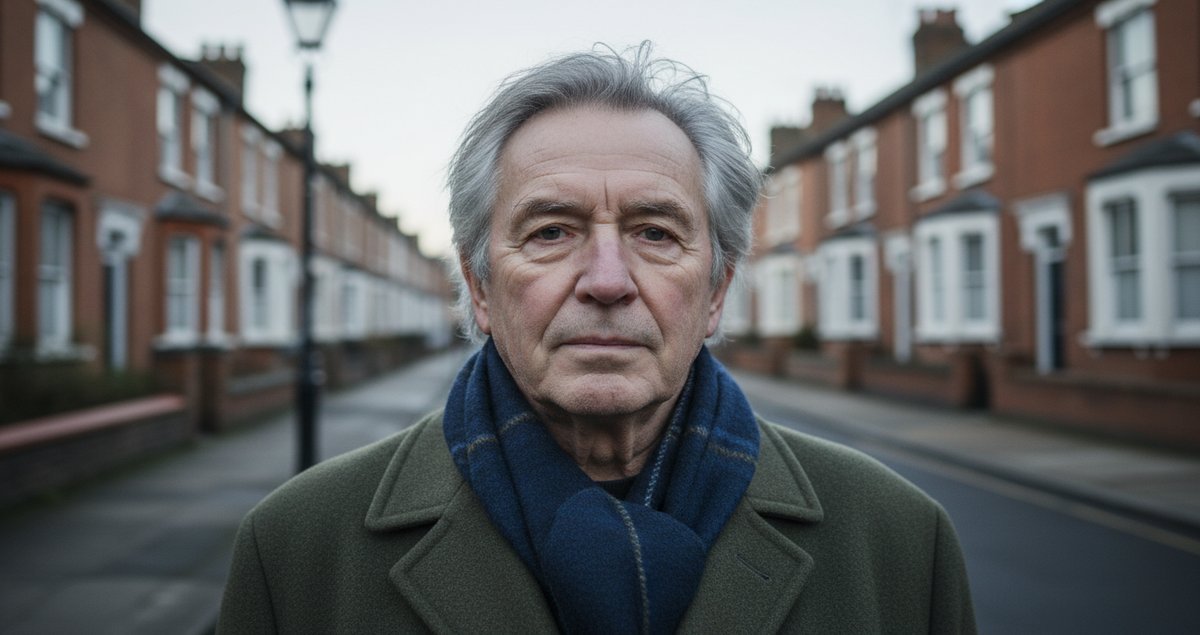

There is an odd, quietly stubborn truth beneath the generational chatter: brains shaped in the 60s and 70s do not process pressure the same way many younger people do. This is not sentimental nostalgia or a neat headline about resilience. It is a braided set of life histories science can measure and stories you can feel when an older colleague stays calm at a crisis and a younger one frays. I want to argue that the wiring of those decades produced patterns of response that still show up under modern stressors.

Not a single mechanism but an architecture

When I say brains shaped in the 60s and 70s I mean people whose formative years fell in those decades. These individuals grew up amid particular social rhythms education models and economic expectations that altered trajectories of stress exposure and coping. The mind is not a tidy box where good coping sits on one shelf and poor coping on another. Instead think of an architecture built from repeated experiences. Early adulthood, job stability labour norms parenting styles and political moods all left traces. Variations in occupation and wealth matter but they are only part of a more complex blueprint.

Experience stacks memory like bricks

One reason these brains respond differently is sheer exposure. People who entered adulthood in the late 60s and 70s often experienced long stretches of workplace stability fewer abrupt career pivots and social expectations that rewarded stoicism. Repetition changes networks. Neural circuits involved in threat appraisal and emotional regulation are sculpted by what they meet. Repeated low level stressors seasoned with predictable rituals teach a brain to expect recoveries rather than perpetual emergency.

Culture as a slow neuromodulator

Culture seeps into biology gradually. Schoolrooms that emphasised deference and regimented schedules the rise of commuting routines and a kind of public stoicism around emotion all nudged neurochemistry. That does not mean brains became less plastic. They did not. It means plasticity operated in an environment that rewarded particular responses. Hormonal cascades and learned habits crept into daily life; the result is not a deterministic caste it is a bias the brain carries into pressure situations.

Evidence and a careful claim

Researchers have documented cohort effects over decades showing that life outcomes and mental patterns can differ by birth period. Some studies hint that people born in certain eras report distinct stress exposures and health markers. We should not confuse this with biological immutability. Instead think of cohort influences as shading the canvas of how a brain tends to orient in novel pressure. The claim here is modest and practical: cohort shaped contexts alter the distribution of coping styles and related neural signatures.

Why pressure elicits different behaviour

Two practical differences tend to surface. First the threshold for interpreting uncertainty as catastrophe. People from the 60s and 70s cohort often interpret novel threats with a calibration that assumes eventual resolution. Second the behavioural repertoire for action. Where a modern job market favours rapid pivoting and visible emotional engagement those older patterns favour measured response and an internal review before outward movement. That measured pause is sometimes read as immobility when in fact it is a different tactic.

Personal observation

I have watched teams crumble and also watched older managers navigate a meltdown with an eerily patient focus. The patient focus is not always better. It can slow adaptation. But it is also less likely to amplify panic. I have no illusions that one style is uniformly superior. It is context dependent and often misunderstood by younger colleagues who use speed of reaction as the single metric of competence.

In a pandemic era study older adults reported feeling calm more often than younger people and were less likely to report negative emotions like anxiety according to Laura Carstensen Professor of Psychology and founding director of the Stanford Center on Longevity Stanford University.

Structural differences and life course health

There are measurable correlates. Longitudinal work shows that early life conditions predict adult brain age variability and cognitive trajectories. Life course exposures from childhood nutrition to midlife work patterns leave fingerprints. A brain shaped in the 60s and 70s carries those fingerprints. They influence metabolic responses inflammatory tone and stress hormone regulation. But again this is probabilistic not categorical.

The paradox of reduced reactivity

Here is a paradox. Reduced emotional reactivity can be protective for momentary crises but can also blunt rapid learning when environments change quickly. People from these cohorts sometimes struggle with novel social choreography such as the always-on communication demands of recent years. They cope well with discrete emergencies but less well with chronic unstable feedback loops that demand constant reinterpretation.

Workplaces and misunderstandings

Most organisational conflict I see is partly generational misunderstanding. When a team member stays silent in a meltdown others assume disengagement. Yet silence can be a conscious strategy accumulated over decades of experience that says wait listen assess. That strategy clashes with cultures that reward visible hustling. The result is friction not because one person is wrong but because the system misunderstands a different adaptive logic.

Policy and practical thinking

Policy that ignores cohort differences tends to be clumsy. Training programmes that presume a uniform stress response miss the chance to capitalise on complementary strengths. Older employees often bring deescalation skills and long view judgment. Young employees bring speed and innovation. Notice the complementarity instead of asking one group to imitate the other exclusively.

Open ended reflections

It is tempting to look for a single fix to bridge generational response gaps. That temptation is sterile. Instead imagine small design changes a meeting structure here a communication norm there that respect different tempo preferences. And accept uncertainty: these cohort contours will shift as those born in later decades age. The lesson is not to fossilise differences as destiny but to recognise patterns so we can work with them rather than against them.

I do not want to romanticise resilience nor to excuse rigidity. I want to pick apart a pattern so we can see how to move inside it. When a senior colleague breathes through a crisis it may be wise to ask whether patience is a learned advantage or a deferred avoidance. The honest answer is often both.

Concluding provocation

Brains shaped in the 60s and 70s respond differently to pressure because they were forged in different social metallurgy. That metallurgy altered exposure patterns learning environments and the social rewards for particular behaviours. We are not stuck with those results. But until we notice them we will keep misreading competence as temperament and mistake context for character.

Summary table

Key idea Brains shaped in the 60s and 70s show cohort influenced patterns of stress response.

Why it matters Misunderstanding these patterns fuels workplace conflict and poor policy design.

Main mechanisms Repeated exposure habits cultural expectations and life course health influences.

Strengths Measured calm and deescalation skills in crises.

Limits Slower adaptation to constant novel feedback and always on demands.

Practical take Design mixed tempo teams and create meeting norms that respect different response styles.

FAQ

Does this mean older people handle all pressure better?

No. This is not a blanket statement about superiority. Older cohorts often excel at certain pressure types such as discrete emergencies where measured evaluation wins. They may struggle with prolonged ambiguous stress that demands rapid and continuous shifts. The point is pattern recognition not ranking.

Are these differences fixed biologically?

Not fixed. They are probabilistic and shaped by life experience. Neural plasticity continues through adulthood though the substrate of experience biases likely responses. Social environments and targeted learning can shift habitual reactions even late in life though some tendencies are deeply ingrained.

How should managers respond?

Managers should stop equating visible agitation with productivity. They should design roles that combine the quick iteration of younger staff with the tempering hand of experienced colleagues. Simple structural changes like clearer asynchronous update norms and decision checkpoints can reduce conflict and make pressure handling complementary.

Does the era someone was born in outweigh personality?

Personality still matters greatly. Cohort effects interact with personality not replace it. Think of cohort influence as background shading while personality is the foreground brushwork. Both interact to produce individual differences in pressure response.

Will the next generations look different?

Almost certainly. Each cohort carries unique exposures economic cultures and technologies that shape learning. The rise of digital connectivity and precarious labour will leave their own marks. Observing these shifts carefully is more useful than grand pronouncements.